Black Hills Research Symposium Keynote Presentations

2023 Research Symposium Keynote Speaker - Transcript

Charles Lamb

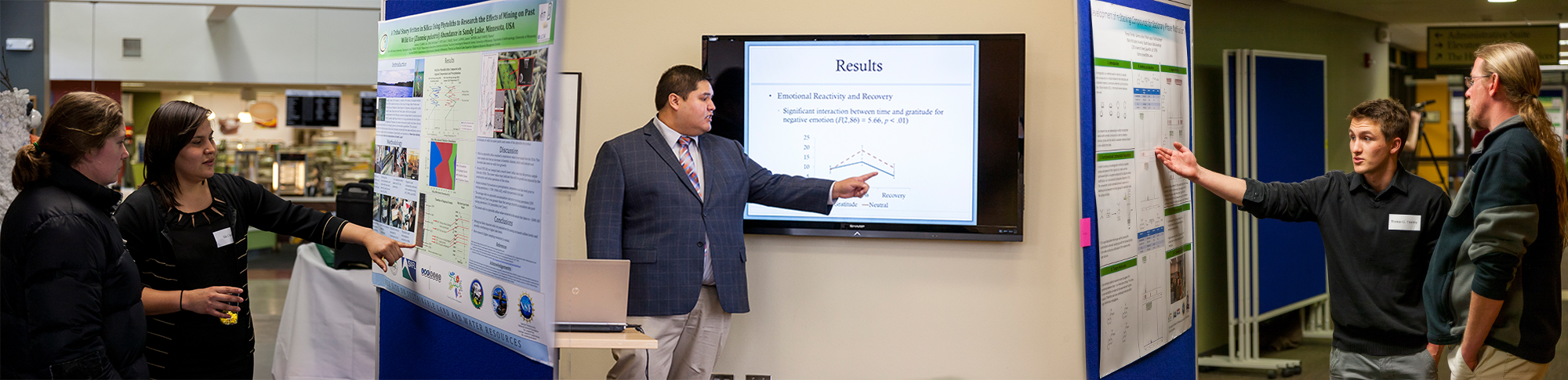

Welcome folks, I'm Charles Lamb. I'm the chief research officer and a biology professor at BH. And it's my pleasure to welcome you all and thank you for attending the Black Hills Research Symposium keynote panel. It's a little different this year. The discussion will be breaching research, career, and community. And I'd especially like to thank those of you who didn't need to be bribed by your professors to show up today. I'd also like to thank the students and faculty who presented talks or posters at the symposium. I hope you guys had a chance to see the presentations yesterday because it's always excited to see the quality and the diversity of the scholarship that we conduct here at Black Hills State. And also the enthusiasm of the students as they get to share their research accomplishments. Now I'd like to thank the people who make this symposium possible. First of all, the Black Hills research symposium committee. They work all year to line up the schedule for the symposium, to arrange for interesting keynote speakers, and to persistently send out reminders to get faculty and staff to submit their research projects for the symposium. This event is made possible by the support of President Laurie Nichols and Provost John Kilpinen who provides financial resources that allow us to host our own research symposium, which I'm happy to say is in it's 25th consecutive year. I'm kind of sorry to say that I've been a part of this symposium since it's inaugural year, because that is a long time. Finally, I'd like to thank the keynote panel participants, Bryan Burton, who is a recent- very recent MSIG graduate from BH, Ben Jasinski from SRAM, and Kelly Kirk from Sanford Lab Homestake Visitor Center, and Dr. Nick Van Kley, director of the Center for Faculty Innovation at Black Hills State University. He'll be moderating the panel discussion today, and now I'll turn over the microphone to Dr. Van Kley.

Nick Van Kley

Thanks Charlie. Good afternoon and welcome. I am really delighted to have a chance to share a stage with these three folks and to moderate our discussion for the next, well 50 minutes or so. Our theme today: "Bridging Research, Career, and Community." So this week students and faculty have shared at the symposium their research work. They've shown a really tremendously wide array of research projects and demonstrated really diverse sets of skills, of knowledge, and experiences around research. And as we talk with our panelists during the discussion today, we're going to be exploring how that works, the work of research prepares the ground for change in the communities that we inhabit. And because of the experiences of the three speakers that we have here today, we also have a chance to think a little bit about how research work leads to transformation right here in the Black Hills. I should know that there's been a change to our program. Originally, we had expected Geralyn Church who is the CEO of Great Plains Tribal Leaders Health Board. She was planning to join us, but we heard of Geralyn this morning that she regrettably is not well and can't be here. We're very sorry to miss a chance to have her on the stage; however, we are also very pleased that we have a new panelist who very gamely, quite short notice, agreed to fil Geralyn's chair. So I'll introduce him in just a minute. So let me take a second to introduce all these three individuals. Let's start with Ben. Ben Jasinski is a software engineering manager for SRAM LLC. SRAM, that's S-R-A-M if you're not a cyclist. It's one of the largest cycling component manufacturers in the world with options located in 10 countries, including one local office right here in Spearfish. An office that's also the headquarters for SRAM's corporal brand. Originally from Rapid City, South Dakota, Ben holds two degrees from South Dakota public universities, including a bachelor of science in intellectual engineering from South Dakota State University, and a master of science and physics from the University of South Dakota. At SDSU, Ben was a stand-out student athlete with several accolades, including a university high jump record. Ben was also an assistant coach for Black Hills State University track and field. More recently and in addition to his over seven year career with SRAM, Ben also worked on the team who constructed the Majorana Demonstrator at the Sanford Underground Research Facility in Lead. Ben, welcome and thanks for joining us.

(Applause)

Kelly Kirk is the director of the Sanford Lab Homestake Visitor Center in Lead, South Dakota as part of the Sanford Underground Research Facility. I'm just going to call that SURF from now on to save all of our ears and my tongue. The Visitor Center contains exhibits on the past, present, and future of the service site. The Center also inspires future scientists by hosting K-12 education and public outreach events. The Visitor Center is really what we think of as a third place in public education and community building, a place where the values of scientific research co-mingle with the work of everyday public education. Hailing from Beulah, North Dakota, Kelly holds a bachelor of arts in history from Black Hills State University and a master of arts in American history from Montana State University Bozeman. In addition to her work as director of the Visitor Center, Kelly has served as instructor of history at Black Hills State University, where she was also the primary investigator on the Veteran's Legacy program to honor and develop South Dakota's national cemeteries as sites of public history through the National Administration Veteran's Legacy program. Welcome back, Kelly and thank you for being part of this discussion.

(Applause)

Bryan Burton is a graduate from the BHSU masters of science in integrative genomics program. During his time with BHSU, Bryan worked with the Paulus lab to uncover details about the progression of a form of ALS and Parkinson's disease. Born and raised in Houston, Texas, Bryan earned his bachelor's degree in biology and chemistry from the University of North Texas. Growing up with a congenital heart condition called Long QT Syndrome, Bryan became passionate about genomics and molecular biology. Bryan has conducted research on a variety of projects, studying neurotoxicology, oncology, Covid-19, bacteriophages, and ecological effects of pesticides. He also owns a consulting business called Burton Science and Technology LLC. Welcome, and thank you, Bryan, for being here, particularly on short notice.

(Applause)

Okay. As we begin, I want to encourage our audience to think about questions you might want to ask the panelist. We have a QR code that you can find up on the screen. Use your phones, the camera app to find a link to a short form or enter that URL to get to it. You'll have a chance to name which person you're asking the question of or just a direct question to the panelists as a whole. We're hoping to reserve maybe ten minutes or so at the end to field some of those questions, so feel free to send those in any time. Alright that's enough of me talking. Let's hear from our panelists. We thought we could just start by hearing a little bit about your role and some of your research work. Maybe you can share that with us. And perhaps, Kelly, would you mind starting us off?

Kelly Kirk

Alright. Well, thank you. So I have become the director of the Sanford Lab Homestake Visitor Center, and in that capacity, I wear a lot of hats on any given day. One of my primary goals is to direct and manage a team of incredible individuals who work with me to help create this Visitor Center as a museum, as a site of public history, and to educate all of the visitors who come through- to tell them a little but more about this history of Lead, the Homestake Gold Mine, and the Black Hills, but also talk about the history of science in this space, and of course the future of science that is happening underground at SURF. Along with that [unintelligible] all of the other tasks of managing a facility from running marketing campaigns, hosting public outreach and community events to, you know, doing a bunch of research on facility maintenance and where to invest, right, our next marketing dollars or how to best reach our varied audiences. And so, personally, I'm actually continuing my research that I started and was working on here at Black Hills State, which is the history of women's suffrage here in the Black Hills. That is a story that there's a lot of details here to be told, and then at work I had to really dive into the stories of Lead and the other Black Hills communities and the stories of SURF. And to, again, find ways to tell those stories whether it is a kindergartener coming in or a local individual who would like to here more about what's happening underground.

Nick Van Kley

Ben, I'm going to hand the mic to you and ask you to talk a little bit about your role.

Ben Jasinski

Sure. First of all, thanks for inviting me to this awesome session with these awesome speakers here. So I'm Ben Jasinski. I'm a software engineering manager for a company called SRAM. So if you're a bike nerd you already know who we are. And if you're not and don't like lycra, like most normal people, then I'll tell you a little bit about SRAM. We're the second biggest manufacturing company for components on bikes, so what does that mean exactly? We make everything except the frame. We make wheels, we make drivetrains, brakes, suspension products, you name it. But what SRAM is really known for in the cycling industry is creating innovative gadgets that go on bikes. And that's where my team comes in. So typically you don't think of software and bikes, but my team creates a digital experience for riders and their bikes. So we're responsible for putting electronics in components like power meters- so a device that measures how much power someone puts into their drivetrain. We also are responsible for putting electromechanical systems in drivetrains so you can control how easy or hard you pedal through an electronic actuated button. Pretty neat. But what my team does in terms of research is actually kind of cool. We have a lot of our riders- we have around a million riders that choose to ride with us, and they give us their activities. So we have collected tens of millions of activities over the last seven years, and my team is responsible for analyzing that data and feeding in the information that we get from riders and shoving it into our product development pipeline. So our manufacturing engineers, our design engineers take that information and make their products even better, whether that means changing how we engineer specific parts to make it more- or higher quality, more durable and cheaper. My team is responsible for feeding that information from the data directly from riders into the product development pipeline, so yeah.

Nick Van Kley

Fascinating. Quite a different set of research tasks in your two roles. Over left there- Bryan, you've operated in really quite a few research roles in your time as a student, and you also maintain a consulting company. Could you tell us a little bit about what you do and maybe where your research interests lie?

Bryan Burton

Yeah, so- hi everybody. I'm Bryan. Currently I have my little consulting company, and it's actually different than any of the research I've done in the past. I do mainly GIS funding for conservation and land management, so it's entering metadata on landmarks and giving recommendations for seating and things like that in areas that need to be reclaimed or that don't have enough native species in them. And my current plans are that I've been filling out some applications to biomedical engineering PhD programs and I'd like to contribute to mostly like tissues engineering side of biomedical engineering. So just building different little materials that cells can grow on. It's a lot of times with organ transplant and different regenerative therapy. It's really hard to get cells to adhere and grow in the way that they're supposed to. So those- that's my kind of current occupation and future outlook. I can talk a little but about my experience here at Black Hills State during my masters. I was really lucky. I got to participate in awesome labs where we use human cells. So these human brain cells and we expose them to a toxin that is actually pretty ubiquitous in most ecosystems. Sometimes you'll see a spot- like a sign by a pond that says, you know, "There's dangerous algae. Don't swim in it. Don't let your dog swim in it." So we study a toxin called BMAA, and that stands for β-Methylamino-L-alanine. But basically it's a product from- that the cyanobacteria produces and whenever you become exposed to this, people will develop a certain type of Parkinson's and ALS. So it's called ALS PDC, which is amyotrophic lateral sclerosis parkinsonism dementia complex. And it's just acquired dementia- which actually 90% of neurodegenerative disease is acquired. Only about ten percent is inherited, so there's a huge misconception about where a lot of dementia and different neurodegenerative disease comes from. So my research here pretty much included exposing those human cells to the toxin, and understanding the disease progression, and trying to kind of pin down more of the method of action and dynamics between different cell types, and how they respond to toxin, and how that could lead to the functional diagnosis of this Parkinson's.

Nick Van Kley

Fascinating. Well, thanks for all those stories. It's truly inspiring to think about how broad a range of research tasks this group of just three folks performs and are involved in. We wanted to take some time to look backward now and to think about your experiences as students. Everyone on the stage was a student once, some of use very recently, some of us it's been a while. So thinking back a little bit to your training as a student and as a researcher, maybe you could share with us how those early research experiences have translated to your work in your current role or the work that you expect to do. Are there skills that you learned that you use very regularly or frequently? And what do you remember about developing those skills as a student? And perhaps, Kelly, we could hear from you first.

Kelly Kirk

Thank you. So one of the things when I think about this that really stuck out to me, when we have visitors at the Visitor Center, we always have limited time with them to tell a very complex, nuanced story. There's a lot of information that we can cover in this space. And so one of the things that my history masters really instilled was conciseness. You might not know that by my storytelling, but I had an instructor, you couldn't write more than 800 words. And it didn't matter how many pages that book was, you turned in an 800 word summary every week on what you read, and that was all you had. So that ability to read a lot of really complex information to try and distill that information as a student, and then try and find a way to present that in 800 words or less, because then you had to go around the room and share. So you wanted to come up with something that was unique and different, that was understandable, and covered, right, kind of key, main points, and was understandable even to a late audience- someone who hadn't maybe read the exact same material you had. And so we're talking about presenting information at the Visitor Center, I think that might be one of the key skills that my history degree taught- was about finding that information and then being able to retell it to someone who doesn't have the background context I have.

Nick Van Kley

I imagine that some folks in the room who have done some research work have had those experiences trying to communicate even with just family when you go home on break. How do you make a terms worth of experiences understandable over the breakfast table? Ben, I'm going to hand it over to you. Maybe you can share some especially memorable training experiences as a student.

Ben Jasinski

Sure. I'm going to piggyback off that. One of the greatest skills that I've learned from research days is technical communication. Specifically bridging the gap of people who don't have that expertise. You have to distill down to more consumable bites. So a little bit about me- for my graduate research, I was working at the Sanford Underground Research Facility, SURF, studying dark matter neutrinos and one of the experiments called the Majorana Demonstrator, a great opportunity for local universities here to pair up with a big, well-known colleges like Berkeley, Stanford, and working alongside those great scientists. But one opportunity that SURF allowed us to do is have an outreach of neutrino days. So this is an opportunity for community members to come out. What is going on in my backyard? Why are they putting physics experiments a mile underground? You get the most astonishing questions that are perplexing sometimes, but honestly they're just well-intended. And as a graduate student, I had the opportunity of, you know, communicating what value our science is bringing to the world. And I've actually bottled that and brought it to SRAM, so I'll bring it back to industry. There's people in SRAM that are traditionally just manufacturing focus. They don't know anything about software. So that skill has come in very handy. Just communicating what this digital experience is going to do to enhance the products that they're making, so that's a good one. And then the second skill is communicating with other technical people, right. There's a hundred software developers within SRAM. We're all trying to go to the same vison. Technically writing down all the things that you do so everyone knows we're on the same page as you're reporting.

Nick Van Kley

Great. Wonderful. Interesting how those are really underlying skills that pertain to your fields, but also probably sound very familiar to everybody in this room as a student as well. Bryan you graduated this fall from the MS Program. So assuming that your student experiences are quite recent, quite fresh. Maybe you could share with us a little bit about how you learn to do the research work that you hope to do in a PhD.

Bryan Burton

So, some of the skills that I picked up doing research here and at my undergraduate university I think would be utilizing resources and just learning, like, what resources are available to me and how to utilize them. I think that I've been really lucky to be at some places with some amazing resources and had, you know, professors that have encouraged me to engage with the resources more. And when you're at a university, you're really at a crossroads of a lot of different professions and a lot of people who are experts in a lot of fields. So I think just understanding, you know, how valuable the setting is and knowing that, and being willing to speak with other people that are experts in things, and just how to collaborate I think, and take on opportunities. It's been really useful in school. Like, I've been asked to help participate with projects and then by choosing to engage with these other individuals and help them with their research projects, I've learned so much and built relationships with them and been invited on other projects. So I think that just not taking for granted the amount of opportunity that is at a university and understanding that you're at a place with a ton of resources that a lot of other places, like, in the professional world or industrial world who might not be exposed to such a diverse group of people that are all so community-minded and willing to engage with you. I think also having clear, set goals in what you want to do- that's something that really helped me with my masters program. I feel like in my undergrad I didn't have as clear goals of what was my intention with being here and what is my goal. So in my masters program, I knew I needed to complete a thesis and I knew the steps to complete it. I knew what exactly I needed to do to get published, so having a clear sight of what am I here to achieve. That's another skill that I think will help you in the real world is understanding how to follow steps and just do what you need to do and not kind of get lost in the sauce of just trying to do the most all the time, and just really do what you're here to do. So, I guess that it.

Nick Van Kley

Great, thanks Bryan. All those sound like things that I wish that I could do better. SO thank you for sharing those. We'd like to approach the same question kind of from another angle. Still thinking back about your experience as a student, we'd like to ask what's been surprising about your career and what kind of research work that you do or have recently done is something you wouldn't have predicted when you were just starting out as a student. And maybe how have you adjusted or adapted to those new kinds of challenges for you. Maybe we can start with you Bryan, actually on this one.

Bryan Burton

Okay. So whenever I initially came here in my first semester, I came here to study, like, cell molecular biology and genomics. The program is in genomics, and my first semester I ended up needing to take a dendrology class, and at that time I was really happy, you know, that I get to spend a lot of time outside studying trees. But I kind of wondered to myself how is this going to play into my career with my goals in mind. And now I- I'm so grateful that I did end up taking that class because I, like, we said it earlier that I have this little consulting firm that I was able to open up. In South Dakota it's really easy to open up your own LLC. You can do it for 100 bucks and like 30 minutes to register online. So it's very accessible to kind of get into entrepreneurship here. And so now I've been using all the skills that I learned using GIS mapping tools and different ecology information and the knowledge of native species in order to earn some money after graduating. So I was really surprised that this class that I had taken, which I didn't think would fold into my career, has really given me an amazing opportunity to earn some income and also have a positive impact on the environment here. So don't take any extra side class for granted, and pay attention because it might come in handy later for sure.

Nick Van Kley

Wonderful. Kelly, how about you next?

Kelly Kirk

I might actually just build off of what you just said. When I thought of this question, it really is you don't know course, topic, or skills set is going to come back in your life. So similarly, as you go through college, you have take all of those additional general education courses, and I knew I wanted to be a historian, and I really just wanted to take history classes. I remember being a little bit frustrated that I had to take literature classes and geology, and I just couldn't figure out how geology was going to impact my career as a historian. And I'm so grateful that not only did- we were required to take those general education courses, but then through some of my other coursework as an honors student we took colloquium and those were cross-taught by selection of professors from the three different schools. And so we got to see how disciplines interacted with each other in those colloquiums, which was amazing to watch professors from science and philosophy and English all teach together and approach the same topic in kind of three different ways. But then as a student to kind of be challenged to begin to approach your own assignments from some of these different perspectives. And then as I became a professor, I co-taught with individuals a in other fields. I worked on research projects with people from varied disciplines, and now I work at the Visitor Center, where the open cup provides a great look at the geology of the Black Hills. And let me tell you the Black Hills geology course really has come in handy. And so, similarly, I think I would say it may not always feel when you're in the moment that course will apply to your future goal or get you to that next step, but it is incredible how over life those courses and skill sets, and being exposed to these different topics really does come to your aid later in life and as you tackle some of those projects. And it also kind of gives you that ability to look at a topic maybe from different angles because you can think about how someone from a different field or with a different background might approach the same question

Nick Van Kley

Great. Ben, how about you? What's been surprising about your research work?

Ben Jasinski

Well, I'm going to steal a quote from a great researcher in its own right, Mike Tyson. I think he said, "Everyone's got a plan until they get punched in the mouth." And I think that's kind of my path in research. You always have a plan of- in graduate school I thought I was going to be studying astroparticle physics for the rest of my life. I wanted to get a research lab. I want to make my own research team. I really enjoy neutrino business and dark matter physics, but then life kind of gives you a curveball, and it turns out that that specific thing is not what I wanted. But the actual why is I just like being a part of building something expansive- something that contributes to something. And I ended up landing at SRAM because I'm passionate about cycling. I'm passionate about the products that we make and I think it has a lot of impact in the world, not just for cyclists, but also just how biking in general enhances the world. And the path that you get to no matter where you start, if you're in research or industry. You just got to find the why. What are you passionate about? And once you find that, then you just go all in. So this is more meta than anything, so I apologize. That's been super helpful for me. And just the graduate school and research gives you the tools to learn. And then when you have hiccups or hurdles or obstacles or new opportunities, you can learn. You already had the- all the stuff that you need.

Nick Van Kley

Thank you. Yeah, when we spoke a couple weeks ago, Ben, you said it taught you how to build- taught you how to learn how to learn, right? That was part of the training and I imagine there's been a lot of learning going on as you learn how to manage software teams across the country and the globe. Well, thanks so much for those accounts. So, we know at Black Hills State, and really anybody who's in higher education know that when you're a college student, your faculty can't train you for exactly the job that you'll have. There's too much uncertainty, too much unpredictability in our career pathways. And as we hear all the time, the future's jobs really haven't been defined yet. So it's really nice to hear some of the ways that your college training even when it wasn't a one-to-one match to the work that you do now, you use some underlying abilities that ended up being useful. And it still takes skill and creativity, energy to find ways to make that transferable, right, those skills that you're developing right now. And then along the way you'll find some surprising utility in the class you didn't expect was going to be useful to you. We're getting quite a few questions here in the box so I'm going to move to our last question and then we should have a good fifteen minutes to talk about some of the questions that you folks out there are sending. And forgive me for all preamble here. I'll preach a little bit at you about research. So in college setting when we think about scholarship, we're often tempted to think about folks in the lab or academics or libraries plugging away on data and collecting it- writing research reports- and that sounds like isolated work, or even isolating work. But in reality, when we're researching, no matter where we are, we're really preparing to communicate. We're building knowledge together and we're trying to reach others, and I don't think it's an exaggeration to say that the research work that we do and the research work that you all are involved in really aims to change the world in some fundamental way. So whether it's building a deeper understanding of genetic disease or the discovery of, once again, mysteries or the creation of new technologies that improve cycling performance. Perhaps you could all share some examples or experiences where you saw your research having an impact in the world where you saw research skills or knowledge leading to transformation for people or communities or for society more broadly. And I think if it's okay we'll start with you on this one, Ben.

Ben Jasinski

Yeah, one of the research things that I've done in the last few years is to support SRAM's non-profit called World Bicycle Relief. So WBR is a non-profit that aims to help developing countries have economic mobility by offering them bikes. So we take for granted in the U.S. just the simple fact that we have transportation to our jobs, to schools, to the grocery store. So there's rural areas in Africa that don't have the basic affordance that we have. So WBR aims to basically create these very rural, rugged bikes and offer them to these underdeveloped countries just to help to get them moving to schools, to pick up basic water and groceries for the town. And, you know, [unintelligible] transporting services and goods, right. So one of the things that I had impact on was measuring that actual impact. So we put electronic sensors on a fleet of these bikes to see how they're actually using the bikes. Are they holding up to the rural demands? Are they actually being used at the frequency that we anticipate? So it's really cool to see some of the research that I've done just with the technology that we're building can impact and measure the impact of our non-profit, WBR. So that's really cool.

Nick Van Kley

What do you see as the possible outcome of this research? What would that be?

Ben Jasinski

Yeah, the outcome there is creating better, more efficient bikes and having more impact in those communities- because we have a theory that that's going to help with the economic mobility of these rural areas. But you have to measure it. So the technology that I've helped deploy is the measuring stick that impacts what we can steer and improve- all that.

Nick Van Kley

Right. Maybe you can also share some of the maybe less global [unintelligible]. What are some of the more [unintelligible] technical tools that you're building and what impact does that have on cyclists?

Ben Jasinski

Sure, yeah. So in general, SRAM, like I said before, is on the innovative things. So my team specifically supports our very high-end products. So the professions that typically buy our products are dentist, so we have this funny things of these are dentist bikes- so they're like ten grand a piece. So we try to push the envelope of innovation but that's only to be able to trickle down that technology to the masses, right. So you have to start somewhere. It takes a lot of resources to innovate, so usually the high-end eats that development costs, but the end goals is to push that technology so everyone can use it. We make it cheaper, package it better- and the influences of that is cyclists just have a better experience on their bike. If you ever experience electronic shifting, it feels really good. And when people spend more time on bikes, the impact is better physical and mental health. If you've ever ridden your bike for three hours, you'll know that. And less reliance on fuel based transportation, so more people commuting. So that's the triple down effect of my time. Yeah.

Nick Van Kley

Thanks, Ben. All right, Kelly. Can you share with us a little but about how your work as the Sanford Lab Homestake Visitor Center has a public impact?

Kelly Kirk

Yes. So one of our main goals in the Visitor Center is to inspire curiosity, right. We want everyone who comes to the Visitor Center to ask more questions. Ask us about the geometric formations of the open cut. Ask us more about the ring in the parking lot and what that means and why we have it there. But where does that come from? What was it used for? And them, you know, be curious when you discover that it was part of a Nobel Prize winning experiment that happened underground in South Dakota. And so I think one of the things that our team is really focused on is trying to come up with a collection of opportunities, offerings, and programs to try and encourage and inspire curiosity and lifelong learning for all of our visitors. And so whether that is partnering with the education outreach team to host field trips and do activities for schools who come and visit, or creating an Ask a Scientist program. We discovered during event signature days that visitors love to ask questions about the science and about what's happening, and they do want to talk to someone who's been involved hands-on, and so we partnered with the science department and once a month, one of our scientists is gracious enough to spend the day at the Visitors Center and visit with guests. And they have visited everyone from students to tour groups. We have homeschool families who bring their students specifically on Ask a Scientist day so their students can engage with scientists at SURF. We are also expanding some of our cultural programming. We're curious about the history of this space. And so we sponsor Author Talks, and so there's- try to create, write a series of dosage orders. We have a trolley tour that we offer, and so every year we write that differently so that someone can have a unique, repeatable experience. We had a really good time last summer on the trolley. They want to bring their family this summer. So we do more research. We pull that story together in a new way and then tell that to the broad audience that comes to the Visitor Center. So it's really neat to see when you start combining the stories of history, the stories of place, along with the story of the sciences occurring, currently- the ways in which your audience engages. And we have a lot of repeat customers, but we also have a lot of people who share their experience with friends and family. And so, you know, we keep quite a bit of data about our visitors- why the visit, how did they hear of us. And the number of people who say it was because of friends or because, you know, they heard that this was a place to learn- it was really encouraging, right, that we're moving in the right direction with that kind of catalog of offerings and programs. And so it's really neat. I think one of my favorites- and I will actually give education outreach the credit- they went to a school- and I apologize, I don't remember- but it was my fourth or fifth grade classroom. And then the student told their family about their experience with education outreach at SURF, and they just really wanted to come and

visit SURF. So they came to the Visitor Center last summer as part of their summer vacation. He was probably about ten and he came up to the front desk and he asked where his internship application was because he wanted to start working with SURF. And so you see the way in which those opportunities inspire that curiosity and that desire to learn more.

Nick Van Kley

Thank you. You know, when I was preparing for this I sort of imagined that the answers from you two would be- that there would be a shorter timeline between research action and impact, but you're really talking about sort of lifelong interests and global social change. These are really large time scales for the effects of your research. And Bryan, I imagine that some of the research work that you've been involved in the lab is similar, right? That you're doing work that might lead many years down the road after many more studies, implementation, and treatments. Or, you know, new understanding that can lead to change way down the road. Maybe you could talk a little bit about what some of those impacts might be fore the work that you either did as a student or hope to do in the future.

Bryan Burton

Absolutely. So here at BH, whenever we were investigating the effects of this toxin, we also investigated the effects of some potential therapeutic options including some antioxidants and other compounds. But we found out some surprising data that some of these commonly-used therapeutic options may have other effects that are not beneficial depending on the cell type. So, we found out that, you know, using the antioxidant on the cells whenever the cells have been exposed to the toxin- for some cells, like the neuronal cells, it helps them live better. But for the glial cells, it helped them mutate and become even more problematic than they were before. So we kind of are flushing out some of the things in the lab about, you know, what would be some appropriate treatment options and how could that impact people later down the road. We also- the cells that we use are human cells, but some of them are also cancerous cells. So the cells can act as a model for this dementia complex, but also they can act for a model in oncology. And so we learned a little but about how maybe these therapeutic options could affect cancer treatment as well. Also, in my undergraduate experience, I was lucky enough to participate in the Howard Hughes Medical Institute SEA-PHAGES program and I was able to isolate and annotate a virus that I got from a dirt sample by a stream close to my university that I went and collected. And it ended up being a temperate phage, which means that the phage has the ability to modify the host genome. So if y'all don't know what a bacterial phage is, it's a virus that infects bacteria. It looks like like a [unintelligible] on a spring with little spider legs. You've probably seen an illustration of it of course, I don't know. So that was kind of exciting to know that I got to pick it out of the dirt and now it's sequenced and there's ongoing research projects with the phage. And I could have huge implication for bioremediation. So if you have like bodies of water that have like a flesh eating bacteria or something in it, maybe you could use a phage to target only that bacteria and not disrupt the ecosystem by using some kind of chemical to clean it out. Or maybe even with antibiotic resistant bacterial infections in humans or animals, you could use phages to isolate what the pathogen is and attack just that pathogen and modify a genome so that it doesn't live or anything like that. So those are some of the implications of the research that I've participated in. And them something that's more of like an active things that I get to see immediately is like with this GIS mapping and conservation and land management that I've been doing through my consulting business. It's really awesome to see, you know, that this- some of the native land in the Black Hills is going to be able to receded and I can see where the land is being managed, which helps with the longevity of the ecosystem. And so those are some pretty immediate impacts, and I really love the outdoors. And I'm passionate about having a place to spend time outside in, and so that's pretty cool, like, immediate impact.

Nick Van Kley

Thank you. I'm going to turn to some audience questions now for a little bit. And I'm going to start with a question from a student, S., who asks, "As a student, how did you start pursing a line of research?" So I think that's an invitation for you to think about those early moments when you started to have an inkling that that was the direction you wanted to go. And I don't want us- I don't want to spring this on anybody individually, so I'll let you choose who goes first on that one.

Bryan Burton

I- I can go first for that one. I remember it was actually my first week of orientation at the University of North Texas. Someone came in- they were one of the graduate students in the phages lab and they were saying that they had two open spots for new researchers, and I remember, like, running across the room, like actually running across the room. And the wasn't enough, like, applications, like, because I was at the back of the room and it was a full room- there was like 40,000 students at my undergrad university. So it's really competitive to get into research, and like I said, I've always been interested in research and everything, especially because of my heart condition. And I benefited from recent advancements in technology that ended up saving my life, so I was just really interested in doing biology and always loved science in high school. But I remember running across the room and then I got an application- or I didn't get an application, but then she was all moved by how I ran across the room and kind of embarrassed myself. So she asked me for my email, emailed me an application and I ended up getting accepted to the lab. And, yeah. Just working in that lab I got to use a lot of new techniques that really excited me, but it was a little old school, like we had flames for sterilizing our loops. We had to work under the flame, and I learned all about aseptic technique, and I made some really good bonds with my lab mate in there. And we had so much fun, like, going to conferences, and getting a hotel already paid for, and there's a hot tub at the hotel, and I ended up winning an award at one of the research presentations. And I got a little bit of money from it, so some of those, like, built-in perks I think really helped me be excited about it. And then feeling like I was actually working towards something that could be impactful on a really big scale, you know. Even though I'm working in this tiny little room doing this tiny little thing under a microscope, it could have huge impacts. And later I could be like, yeah I was part of that. And so I think that's what got me really excited.

Nick Van Kley

An iconic memory of sprinting across a room of people to get an internship. That's wonderful. How about you, Ben or Kelly?

Ben Jasinski

Just- so the question was, "How do we get into research?" Yeah.

Nick Van Kley

It was- go down this road.

Ben Jasinski

Yeah, sure. So for me personally, I just wanted the means to flex my nerd muscles, so I talked to a lot of my professors at SDSU and got acquainted with the research labs that they are associated with. So that's one really good way- just, just talk. Talk to your professors, see what- if anything resonates with the research that they're conducing and if it aligns with your passions. And then try a lot of different things, right. There's- I went from electrical engineering to nuclear physics, to just astrophysics, to bike parts. So if there's a lot of range of nerd muscles that you can flex. So, I'm going to coin that. Nerd muscles.

Kelly Kirk

I think I might have kind of fallen into my first research project as an undergrade because it was assigned to me as part of my internship program. And so it was working for the North Dakota State Historical Society, and I had to help develop some exhibits, some tours, all kind of around one theme that we were building on for the summer. And that really got me interested in local history and that kind of became a theme. I'm an intern for Deadwood history and again was encouraged to write a walking tour, so it dove into a lot of local community stories about Deadwood. So by the time I got into my master's program, I'm trying to uncover local histories. That was something that I discovered that I really enjoyed, and speaking of the nerd muscle, I also have been really kind of enjoying getting to know the place where I was living because you kind of saw locations and spaces in a different way. But I don't know if I was exactly thrilled when my internship supervisor kind of first handed out this research project. And there was a local women who we had a picture of in the archives, but we had no information about her. And he was just kind of like, "We would really like to- we know she- we know her name. We know when she came to Bismarck. We think there's a bigger story here because her photo is here in this collection. Can you build up her story?" And, I tell you what, I was not prepared for that. But it was a great scavenger hunt, right. It was a great puzzle to put together over the course of that summer, and built up. And so I kind of fell into that local history niche, but I absolutely loved it. And so, as you see, you kind of try on a few different things. But either having- or talking to professors or an internship about ways you can get involved, that's a great way to kind of see what's out there. And then you can learn from someone who's already doing some of that work. That's helpful, too.

Nick Van Kley

Great, thank you. I'm going to ask a question here from a colleague of mine, Alan. And Alan asks, "Are there any research or study skills that you wished you had focused on as an undergraduate that may have helped you in your current goals? Things that, in retrospect, it would have been nice if you would have been paying a little bit more attention to.

Bryan Burton

So, especially getting into my master's I started to understand how important software and coding and things like this are in biology. And I was always like one of those biology students saying, "Oh, haha. I don't have to take the coding class. I don't have to take that super high math class or whatever." But now I'm getting like, a little bit deeper into the field. I'm starting to understand, like, I really should have thought a little but more about the marrying of technology and math with also like the more wet lab and science, biology-based things. And that's something that I'm kind of insecure about now, kind of entering the workforce, is like that I don't have a ton of experience using coding languages or even just like understanding how to utilize and build different pipe lines using different softwares. So I think I would have really just want to focus more on some of technological aspects and understanding the technology, and I know that might be kind of hyper-specific to me and what I do, but I think with a lot of industries, learning how to, like, engage with software and understanding more computer science would probably be a really big strength. Especially when you see people, like, now in high school that can take all these software coding classes instead of a foreign language and things like that. In my undergrad I minored in Spanish. I really wish I would have maybe minored in computer science or something like that that would be a little more applicable to my career.

Ben Jasinski

Oh let's see. One skill that I wish we developed a little bit more in the research side, graduate-level side, is just how to collaborate with individuals. It's really hard to have just a specific class around that, but when you're working in a large, collaborative research project like we did at SURF, they don't teach you how to interact with other brilli- well, I'm not brilliant- but brilliant people, right. So, and there's some nuance on the soft skills that maybe don't- it doesn't come natural to a lot of people. But in industry, like, you're thrown into the mix and I've been fortunate enough to lead a team of engineers. But I've had to learn along the way on how to lead that team.

Kelly Kirk

There's so many. It ranges, but I wish I had taken more stats courses. Actually, when I was in grad school for history, there were some departments that actually still considered stats a foreign language for historians. They really did not assume that we knew math. But when you start doing a lot of data analysis, having that background can be incredibly helpful as you're creating your arguments and sharing information and breaking down data. But kind of the more, maybe like a soft skill or one that's a little bit harder, I was learning how to ask the questions. You know, it was- it can sometimes be really hard not to be the expert or not even know where to begin in your questioning. And, you know, there will be days where something will come up and I'm not even quite sure, you know, where to start the process of questioning, much less kind of who to start that with. And so kind of being willing, right, to just kind of go out there and start asking the questions. And your question will refine itself over time, and you will find really wonderful, gracious people who will lead you towards the person who can help you answer this question, who is kind of the end of the puzzle. And so, having kind of the courage to go out and do that and kind of learn the process of learning what you need to know for that specific task or in the moment.

Nick Van Kley

Hey, thank you. Yeah, it was found, like, they really resonate with the underlying purpose of a liberal arts education, which I love to hear of course. Maybe we could pick up on what- what you mentioned, Ben, about collaboration. I'm sure that's been a major part of almost all the research work that you've done, Bryan, and I know it's been true for you, Kelly. How is collaboration fit into your,- your life as a researcher?

Bryan Burton

I think that it's like you said, pretty essential, especially in biology in genomics. You really have to talk with a lot of people because everyone's very hyper-specialized in their industries. Even for my master's project, we're always talking to different people at the different schools in South Dakota, and the way that our lab is set up here at BH, where we have a core, and there's a proteomics core in another South Dakota State University, or yeah. So the different universities will kind of pull resources within different specialties so that collaboration is really built in. I think it's really important to build the friendships, too. I'm probably more one of the more pro-social, like, lab rats I guess you would say. I really love, like, talking to people and getting to know people, and it's one of my favorite things in the lab. I think you meet a lot of interesting people and people from different areas. That's another really awesome thing about science and working in science is I've been able to meet people from all these different countries and backgrounds, and you honestly learn so much even just about the world and the people because of the collaborative nature of things. And I built a lot of lasting friendships and, yeah, just talking to your lab partner and stuff and you don't even know who's going to end up being your collaborator down the line, so you don't want to take anybody for granted, even if you're in a position of power over them or if they're just a normal peer. It's really important to understand everybody's value and really engage with them because everybody knows something that you don't, and the only way that you're going to be able to know what they know is if they decide to show it with you. So you have to make yourself open and available for them to want to collaborate with you, also. So I think the power of a smile can really bring you a long way, especially in science and other fields where collaboration is really like, you know, these amazing teams who solve things. A lot of times, it's not individuals winning awards, it's groups.

Kelly Kirk

We're actually working on a project right now to create a new educational activity for students when they come to the Visitor Center. And it means that you get the opportunity to collaborate across almost, I think, every department at SURF. And so my team did the original brainstorming for the program and the types of questions we think we wanted to ask and what we wanted people to engage with when they're at the Visitors Center. I have only ever taught college students, so I do not know how to write engaging questions for a different aged audience or make sure that the questions and the education opportunities are grade-appropriate. And so we're partnering with education outreach team to work on creating these activities then for specific age groups. So that, whether again, this is a kindergartener coming in or a teenager, we have something for everybody. And along with that, then we have a collaboration with the science team to make sure that we're phrasing things correctly and that we're getting kind of to the hardness of the science that's occurring underground. We're working with the communications department because they're going to help me with design an layout, because if you leave that to me it will not be nearly as user-friendly. Times New Roman size 12. (Laughs) And so through the course of this, it's really wonderful because you get to work with people from all different background who are all trying to work on kind of one finished product. And at the end, it's going to be an incredible opportunity for any student who walks through our doors. There's going to be a lot of hands that have been part of that process. Again, no one person is really responsible for this and so it's a large team that's really neat to see when you can have all those brains working together what is developed, and this is far better than what, you know, I would have developed myself.

Nick Van Kley

Thank you. Just- the inspiration for students in the room when you have that big group project show up in the middle of winter, remember? That is great training for what will be the heart of your work as a professional developer. So, lean into group work. Okay. I think those notes on collaboration are a good note to end on for our panel. We're also out of time. I wanted to thank all the students in the room and faculty who presented their work yesterday during the poster presentation and the panels. It was really inspiring to hear about some of that work and to see some of that work emerge from collaborations among students and between students and faculty. And a really hardy thank you to Bryan, to Kelly, and to Ben for sharing your experience. A round of applause for our panelists please. I'm sure the three of them will linger here for a minute if you want to come up and say hi, introduce yourself. So you can do that, but thank you for joining us this afternoon. We appreciate it.

2024 Research Symposium Keynote Speaker - Transcript

24th Annual Black Hills Research Symposium (2022) - Dale Claude Lamphere

23rd Annual Black Hills Research Symposium (2021) - Dr. Shankar Kurra and Dr. Nancy Babbit: "A Candid Conversation about COVID"

22nd Annual Black Hills Research Symposium (2020) - Dr. Miro Haček Address Title: “Democratic Consolidation as a Key Aspect of Peacekeeping in the Western Balkans"

21st Annual Black Hills Research Symposium (2019) - Dr. Vincent Youngbaeur Address Title: "The Importance of Media Literacy Education in 21st Century America."

20th Annual Black Hills Research Symposium (2018) - Dr. Eric S. Roubinek Address Title: "Fascism, Race, and Empire."

19th Annual Black Hills Research Symposium (2017)- Dr. Kyle Whyte Address Title:"Indigenous environment justice and climate change: Stopping pipelines, decolonizing climate science, indigenizing our futures."